Blast From The Past – Ernie Cage

Blast From The Past – Ernie Cage

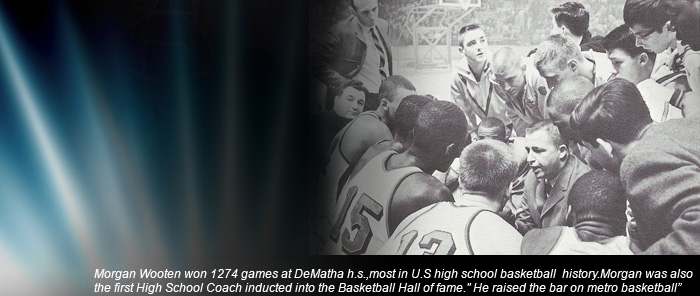

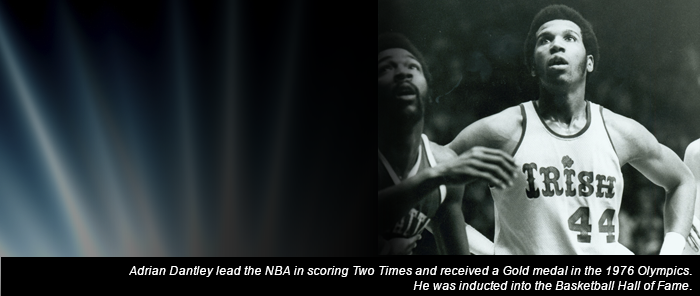

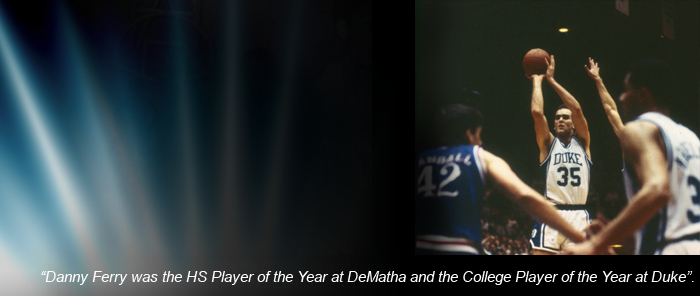

Mention DeMatha High School, and most basketball fans think of Adrian Dantley, Kenny Carr, Danny Ferry, James Brown, or maybe Derek Whittenburg. One name that often gets overlooked these days is Ernie Cage. That’s a shame. In the late 1950s, Cage was a three-time All Met guard known for his deft long-range shooting and then astonishing 2,038 career points. Cage also holds the distinction of being former DeMatha coach Morgan Wooten’s first superstar. Poor grades scuttled his promising college and dampened his legend. But, as Cage told the Washington Evening Star in March 1976, his life turned out just fine. Cage passed away in 1997. He was 58 years old.

----

Ernie Cage Can Never Be Right, But He Isn’t About To Change

In March 1958, Richard M. Nixon was touring South America as vice president. There was a law against women appearing in the town center of Greenbelt, Md., wearing pedal pushers (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedal_pushers) or hair curlers. And Ernie Cage, a senior at DeMatha High School and the most sought after basketball player in the area, wore a crew cut.

Now, Nixon has just returned from a visit to Red China as a private citizen, Greenbelt lets women wear pedal pushers and hair curlers just about anywhere but Ernie Cage still wears a crew cut.

He’s also sill active in basketball – not as a player, but as a referee. He works more than 175 games a year, ranging from Atlantic Coast Conference contests to midget competition in boys’ club ball. He will one of 12 referees working in tonight’s Maryland State High School Championships.

But basketball is only Cage’s hobby. He is a policeman in the District’s traffic department from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. daily.

AS A LOT of his friends point out, there are only two possible explanations why anybody would want to hold down two jobs where he’s never right at the same time. Either he is masochistic or crazy.

Cage is neither. “I wouldn’t trade with anybody,” he says. “My father was a policeman and I joined the force because they needed people. It was a good job with respect and it gave me a chance to help others.”

“I became an official because I simply couldn’t keep playing sports because of my police schedule. Refereeing gives me a chance to stay active without interrupting that schedule.”

“Oh, once in a while I wonder what I’m doing, but I think most people do that. I still love my work and enjoy it. That’s a hell of a lot more than some people can say.”

STILL, THERE ARE times that even Ernie Cage wonders about his choice. “There’s absolutely no way you can ever please anybody holding down these two positions,” he says.

“You’re always wrong, whether you give out a ticket or you call a charging foul. At least in other professions you’re right some of the time. With these two jobs, though, there’s no way you can win.”

Cage has worked for the Metropolitan Police Department for 13 years, been a basketball official for 10, a baseball umpire for nine and a football referee for eight. And he has taken every kind of abuse imaginable.

As a policeman, he is taunted and cursed at. Once, he was thrown through a bay window while trying to break up a fight.

As a referee, he has not been thrown through anything. But he has had everything in the stands thrown at him.

To a lot of people – particularly to those who watched him play at DeMatha under an obscure new coach named Morgan Wooten – Ernie Cage will never be anything but an athlete.

Eighteen years ago, Ernie Cage was a three-time All-Metropolitan guard and a superb baseball pitcher. College basketball coaches and baseball scouts spent more time hammering on his door than hammering on chopped-sirloin specials in corner diners.

“I’ve had some great players and I’ve watched some great ones come through this area,” said Wooten, who is still coach at DeMatha. “But of all those players, I’d have to say that Ernie Cage was the best pure shooter I’ve seen. I know that he helped launch my career.”

“The thing about Ernie is that he wouldn’t take a shot within 20 feet, and he still hit more than 50 percent (54 percent to be exact, while scoring 25 points a game). Only Adrian Dantley had a better career percentage than Ernie, I think. But Adrian was shooting from inside, while Ernie would just bomb away.”

“Why, when it came to foul shooting, I’d even take him over Bill Sharman (former Boston Celtic guard who holds the NBA record for free throw accuracy).”

“He hit 92 percent in high school. In college (Mount St.Mary’s in Emmitsburg, Md.), he made his first 48 attempts and then apologized to his coach for missing his 49th. It seems he had a thumb jabbed in his eye and he couldn’t see.”

“But basketball wasn’t his only sport. He was a tremendous pitcher. As a matter of fact, we won our first Catholic title in any sport his senior year when he pitched three complete games – 23 innings – in six days and didn’t give up an earned run.”

SO WHAT happened? Why didn’t Ernie Cage become a star instead of a policeman? Cage himself admits that he could have made it in big-time college basketball had he just paid enough attention to academics.

“I wasn’t dumb or anything, but I just never hit the books,” Cage says. “I was a superb shooter – I can still put the ball in the hole if I’m standing still – but I couldn’t get into too many schools because of my grades.”

“I wanted to go to North Carolina, and they were after me. In fact, there was a story in the paper saying I signed there. But I couldn’t. My scores were too bad.”

Instead, he wound up at Mt. St. Mary’s. His [freshman] year, he shot 60 percent from the floor and made 90 percent of his free throws. He averaged 20.1 points and made the NAIA All-America team.

Then came more academic trouble.

“I didn’t study or go to class, and I flunked three subjects,” he recalls. “I could have stayed in school, but I wouldn’t have been able to play ball. So, I left.”

He went to Southeastern for a year, but then got married and had to look for a job.

I DECIDED to follow in my father’s footsteps,” Cage said. “I took the Civil Service exam, passed it, and became a policeman.”

Cage still played ball on the side, but his work schedule was so erratic that he finally gave it up.

But he wanted to remain in sports and when a friend suggested he try officiating, pointing out that he could set his own schedule, Ernie Cage finally hit the books.

He studied the rules of football, basketball and baseball, attended referee and umpire clinics, and passed the exams to become an official in three sports.

In addition to refereeing 175 basketball games, he also works about 110 baseball games and 90 football games (including touch football leagues) each year.

“The thing I like most is doing kids’ games,” he says. “I had one game last year where the kids did everything wrong. It was funny to watch them. They tried so hard, but they couldn’t get it right.”

“They were having fun, though, and that’s what it’s all about. That’s what makes it so enjoyable for me.”